If you're curious where you stand in relation to the average amount of debt Americans have as individuals or how we're doing as a country, I've put together these facts and figures from various sources.

You may want to sit down before I tell you the latest numbers of personal debt in the United States in 2021.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the average American debt each U.S. adult carries is $58,604. Seventy-seven percent of Americans have at least some type of debt.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the average American debt each U.S. adult carries is $58,604. Seventy-seven percent of Americans have at least some type of debt.Before you fall off your chair, let's just clarify the definition of debt. The simplest definition of debt is when you owe money - to anyone and for any reason.

Most of us who have debt have agreed on terms of repayment with specific amounts paid for a specific period until the debt is repaid. Usually, interest is added to the debt to make it worthwhile for the lender to lend you the money. Maybe not if it's a loan from mom and dad, but usually.

The most common types of debt in America are:

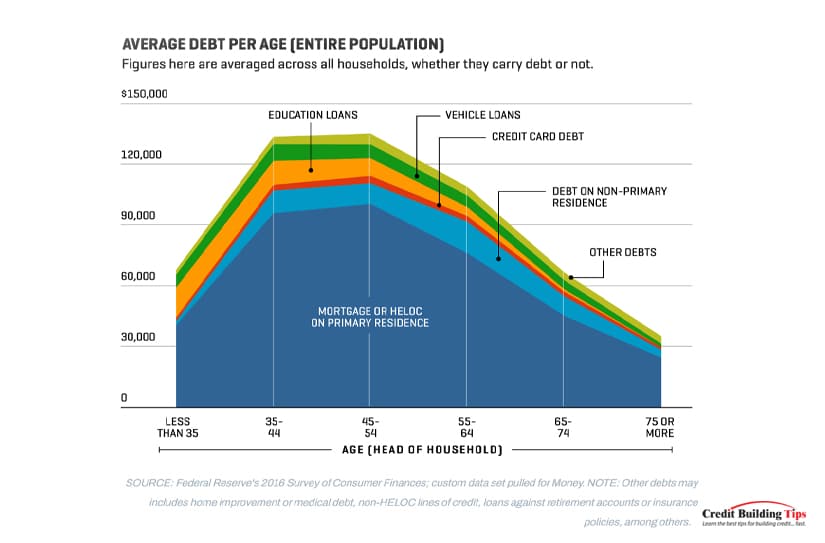

Still from the United States Census Bureau, the average American debt per household in the four categories I listed above is shown below:

| Type of Debt | Debt Total | Average Debt per Household |

| Any debt | $14.96 trillion | $158,209 |

| Mortgage | $10.44 trillion | $202,454 |

| Student loans | $1.57 trillion | $58,112 |

| Auto loans | $1.42 trillion | $31,142 |

| Credit card debt | $787 billion | $14,241 |

| Other | $421 billion | — |

For most of us, paying for some type of housing is our biggest monthly expense. Whether paying rent or a mortgage, a larger part of your monthly paycheck goes to ensuring you have a roof over your head.

Back to the U.S. Census Bureau. They report that Americans with a mortgage make a median monthly payment of $1,595. Mortgages make up 70% of all American debt, which should be a bit of comfort. Of all the debts you can carry, having a mortgage on a piece of land and home still has a great return on investment. It's a debt that most often gives back.

Fifty-one point five million American households carry a mortgage. That translates to 42% of all households with an average mortgage debt of $202,454.

As of last summer, the latest numbers on the total student loan debt sit at $1.57 trillion. If we average this astonishing number out, this means each student owes an average of $38,792 that will need to be repaid once they graduate.

Student loans account for 11% of the country's total debt and are currently the fastest-growing type of debt in the States. To give you some perspective, this type of debt has grown at almost 157% since the Great Recession of 2007-2009.

The impact of this weight on young adults can't be overstated. Many graduates say that their student loans keep them from buying a home (40%) and even considering investing in their retirement (47%). Twenty-one percent even wait to get married because of their student loan debt burden.

Thirty-seven percent of Americans can't afford to buy a car without getting a loan. That translates to about 45.4 million households that carry this extra debt. As of last year, the total American auto loan debt is $1.42 trillion.

Experian reports that the average monthly car payment is $577 for new vehicles and $413 for used ones. The average total car loan debt per household is $31,142.

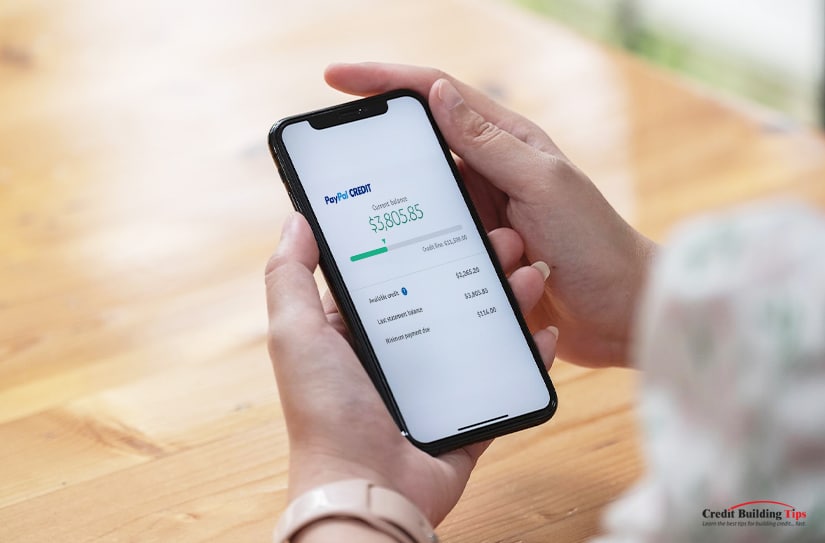

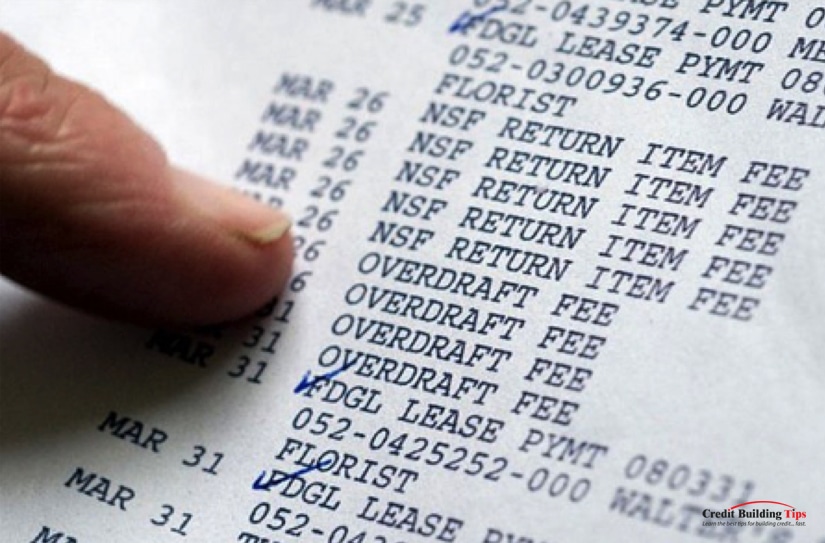

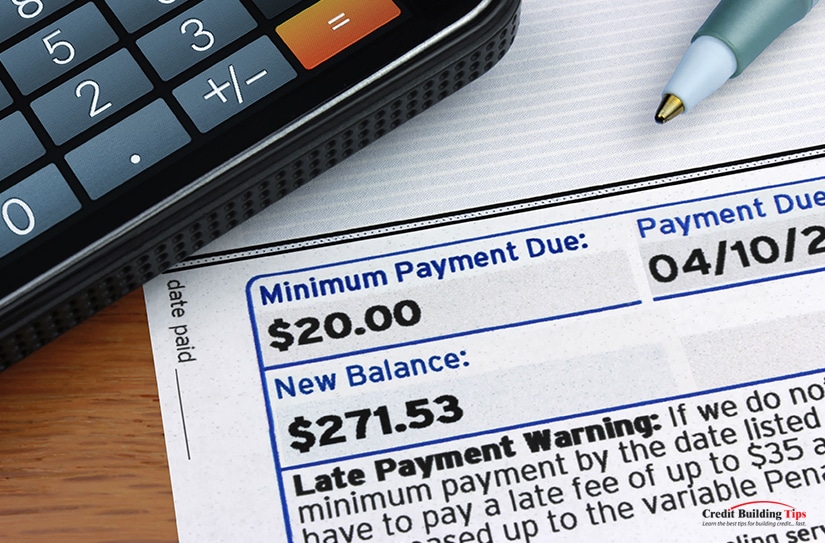

The potential of never getting out of debt is greatest when we use credit cards and don't pay them off in full each month. Eight out of ten American adults report having at least one credit card, and 45% of these carry a balance over to the next month.

Just over 55 million households have this kind of debt, and the average credit card debt per household is $14,241. The total in America now has hit $787 billion in credit card debt.

While you won't qualify for a mortgage, student loan, or car loan unless you show you have the resources to repay the loan, credit cards don't require the same proof. Almost all mortgages, student loans, and car loans are set up with automatic payment withdrawals, which ensures your debt gets paid down without you needing to choose whether or how much of the payment you will make.

With credit cards, you can decide to make the minimum payment or only pay a portion of the monthly statement. Unfortunately, whatever you don't pay will accrue interest — an average of 17.13% will get added to your next statement on the unpaid portion.

If you do the math on the average interest and the total amount Americans owe in credit card debt. Credit card companies can look forward to making about $134.81 billion on interest alone.

And if you're one of the 52% who carries debt and pays interest on your cards, you're part of contributing to that $134.81 billion dollars.

Released at the beginning of this year, Ace Bagtas wrote an article called 15+ Statistics on Average Debt in the U.S., using figures gathered from the last three years.

Based on the average American figures:

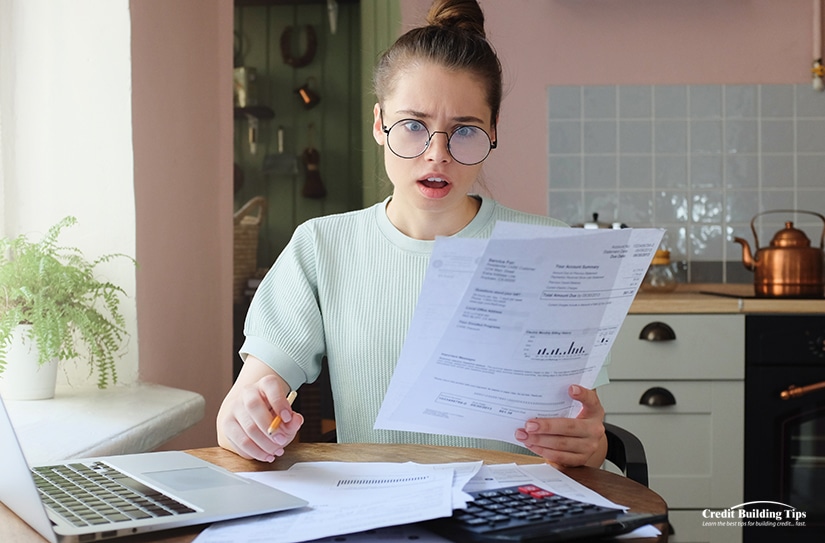

No matter how the numbers are crunched, with 77% of Americans carrying some kind of debt, it's probable that you're one of them. Of course, some debt is better than others, and some debt can lead to problems.

When you have debt, it's hard not to worry about how you're going to make your payments or how you'll keep from taking on more debt to make ends meet. The stress from debt can lead to mild to severe health problems, including ulcers, migraines, depression, and even heart attacks. The deeper you get into debt, the more likely you will face health complications.

Debt can feel free when you're in the rush of buying something, and all it takes is a swipe of your credit card or the scribbling of your signature on a loan document. That's an obvious illusion, even though it can be a powerful one. Unless you have an interest-free loan or a zero percent APR credit card, you will pay hundreds if not thousands of dollars for the privilege of borrowing money.

Any time you take out a loan or buy something you can't pay for immediately, you are borrowing from your future. You hope you'll earn enough in the future to pay for something you bought in the past, and if that something doesn't appreciate in value, you may experience severe buyer's regret when you're still paying years after you've used up what you bought.

The more debt you accumulate, the higher your monthly payments will be, and the less you'll have available to spend on anything else, like vacations or (more importantly) funds for your retirement.

On a personal level, debt can put pressure on your household finances and create a lack of financial security for your family. This is especially true if you're not on the same page as your spouse and find yourself arguing over spending habits.

Getting out of debt may sometimes feel like climbing out of a deep dark hole, but there are tips on how to start climbing.

Every journey starts with the first step, even getting out of debt:

While some financial strategies suggest taking a portion of your income and investing it in a well-balanced, long-term investment rather than paying off your mortgage, that's the only strategy I think works when it comes to managing debt.

For the other types of debt — student and car loans and credit card debt — consider changing your thinking about debt altogether.

When you rely on credit, your ceiling is your credit limit. Once you hit it, you can't spend any more. So you stop. You need to change this.

Your spending limit needs to be the money you actually have in your checking account. Once it's gone, then you shouldn't spend any more. Once you refine your spending plan and learn to follow it, you should be able to always keep a buffer of $500 to $1,000 in your checking account.

That may be a big goal if you're facing a lot of debt, but it is truly one you can reach. And your biggest reward will be the feeling you have once you do, and you're one of the 23% of Americans who are debt free!

Before your toes start to curl when you read the word "dispute," let me reassure you. A 609 dispute letter isn't really about disputing in the sense of creating conflict or having an argument.

Asking for a 609 dispute letter is simply a way of asking a credit bureau to give you the documents that confirm how reliable and accurate their reporting is.

Asking for a 609 dispute letter is simply a way of asking a credit bureau to give you the documents that confirm how reliable and accurate their reporting is.If you find information on your credit report that's not accurate, you can easily figure out why when you get one of these letters. It's important to keep an eye on your credit report, especially if it's dragging down your credit score.

The Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) is the primary federal law that regulates the collection of consumers' credit information and access to their credit reports. This act was passed in 1970 to make sure any personal information contained in the files of the credit reporting agencies is fair, accurate, and kept private.

It also has rules that manage how a consumer's credit information is obtained, how long it is kept, and how it is shared with others — including consumers themselves. If you're interested in some bedtime reading guaranteed to send you to sleep, you can read the entire act here.

While section 609 doesn't come right out and say that you have a right to challenge inaccurate information, it does defend your right to get a copy of all the information in your credit file.

You have the right to ask for:

While that's all good, section 609 doesn't give you the right to require credit bureaus to provide proof of your accounts. They also have to provide a description of the dispute process if you ask for it in writing.

You can argue over any information you think is incorrect or unverifiable. The credit reporting agency is responsible for deleting any information that can't be verified or confirmed. But if the information turns out to be accurate, they don't have to remove it.

You might think that credit bureaus are all about checking and checking again to ensure they don't make mistakes. Unfortunately, they're still human and can type in the wrong information, get numbers mixed up, and generally mess up.

Apparently, the most common types of mistakes that credit reporters make are these two:

Your credit report can also mistakenly show credit card payments as being late when they're not or show utility bills as unpaid when they were really paid.

Errors like this lower many Americans' credit scores. And when your credit score is low, it can affect your ability to qualify for a loan or a credit card. This can be totally frustrating if your credit card score is lower than it should be because of a clerical error.

Even if you do qualify for a loan or credit card, you might have to pay a higher interest rate. If you don't deserve this higher interest rate, you'll be losing money every month.

In some cases, if you're applying for a new job and your employer wants to run a credit check to make sure you're a financially responsible employee, a bad series of entries on your credit report can ruin your chances of being hired.

In the United States, credit reports are created by three big credit bureaus:

These companies package, analyze and put together credit reports and credit scores. Lenders then use these scores to decide whether they'll lend you money.

There's no evidence that sending a section 609 dispute letter is better (or worse) at figuring out an error on your credit report than other ways of checking. If you send a dispute letter and the credit bureau can't produce the information that's being used to calculate your credit score, action must be taken.

If the credit bureau can't show you:

Then they have to remove the disputed item or items because it's unverifiable. Just know that while the FCRA states you're entitled to all the information a credit reporting agency has in their system, they're not responsible for giving you information they don't have in their system. Totally reasonable.

The flaw with just relying on a 609 letter theory is that the FCRA doesn't require credit bureaus to keep or provide signed contracts or proof of debts. This means the information could still be valid and correct, even if the specific documents you're looking for can't be produced. That's not helpful.

First, you'll want to get copies of your credit reports so you can review them for errors. You have the right to a free copy of your credit reports once every 12 months from AnnualCreditReport.com. You can also call (877) 322-8228 to ask for a copy of your credit report over the phone.

A good start is to get yourself organized. If you have a lot of bills that you pay through a loan or credit card, a simple spreadsheet is a great way to get a clear picture of who you owe, how much, and whether you're on track with your payments.

Create a spreadsheet that lists:

You might find it helpful also to identify what type of debt each charge is. Some debts have different rules about how they're allowed to be collected.

The three main types of debts are:

Secured debts are debts that are attached to something of value. Like your car, boat, or your house. Something you can touch. If you don't make payments, these things can be repossessed.

Unsecured debts aren't attached to any material thing. These kinds of debts include student loans, medical bills, or credit card debt.

Priority debts refer to back taxes, spousal support, or child support payments. You can't get around paying what you owe, even if you are forced to declare bankruptcy. Every other type of debt may be wiped out, but these three will stay with you until you pay them.

You'll want to keep your papers in a better place than by stuffing them into a shoebox. You don't necessarily need a fancy file cabinet, and you can just get a sturdy box, invest in some folders, and file the same type of account or debt in its own file.

Mark the account name on the top of the file and put them in alphabetical order. It's the simplest and easiest way to keep track of what you owe and to see if your credit report is accurate.

There's a lot of information online about 609 dispute letters, but there's really no evidence that any one letter template is more effective than another. Apparently, you could write your credit report dispute letter on a paper towel. As long as it includes all the necessary information, can be read, and is true, the credit report must be corrected.

And while you could spend money buying a letter template, you really don't have to. There's nothing special about the format or wording, it just needs to include accurate and complete information about you, plus you need to make sure to include all the documentation required.

Make four copies of the following documents:

Once you have those copies, you'll want to write a letter that includes:

Your name: John Smith

Your street address: 123 Main Street

Your town, state, and zip code: Anywhere, any state, 123456

Your phone number, including area code: 123-456-7890

Today's date: Month, day, year

Subject line: Fair Credit Reporting Act Section 609

Dear Credit Reporting Agency (Equifax, TransUnion, or Experian),

I am exercising my right under the Fair Credit Reporting Act, Section 609, to request information regarding an item that is listed on my consumer credit report:

Account name: Worldwide Collection Agency

Account number: 0987654321

Reason for dispute: Example: This isn't my account/I've already paid this account

As per Section 609, I am entitled to see the source of information, which is the original contract that contains my signature.

My identifying information is as follows:

Date of birth: Month, day, year

Social Security number: 123-45-6789

[Note: If you have a lawyer, state that you have legal representation and provide that person's contact information.]

As proof of my identity, I have included copies of my:Birth certificate

Social Security card

Passport

Driver's license

W-2

Rental agreement

A cellphone bill.I have also included a copy of my credit report. I've circled (or highlighted) the account I want to have verified.

If you cannot verify the account with the original contract, please remove the information from my credit report within 30 days.

Sincerely,

Your signature

Enclosures: Add a list of all the supporting documents you include with this letter.

Once you've made your four copies and written and printed out your letter, you'll need to put together three separate packages and send one to each credit reporting agency listing the account you need to have verified. Keep one set of the letter and documents for yourself.

Equifax

P.O. Box 740256

Atlanta, GA 30374-0256Experian

P.O. Box 4500

Allen, TX 75013TransUnion Consumer Solutions

P.O. Box 2000

Chester, PA 19016-2000

Take the extra trouble to go to your local post office and send the packages by certified mail.

You'll pay less than $7 an envelope at today's postal rates, including a return receipt. A small investment to ensure these packages get where they need to go!

If printing and sending a letter with physical copies seems too old-school for you, you can start a dispute online with each of the three credit bureaus.

While there are no guarantees that a 609 credit dispute letter will help you remove negative information from your credit report, if you are right that the credit bureau has made a mistake on your report, you have the best chance of fixing the mistake (and your credit rating) with a 609 credit dispute letter or by filling in the online equivalent.

The bureau wants to make sure there was a mistake made, and they find the documents required to verify the debt(s) in question and how clearly the items are disputed.

609 letters are the best way to get the dispute process started. Once you've requested information from the credit bureaus, they must give you all the information in your credit file related to the items you've inquired about.

They don't have a choice whether or not to give you the information you asked you. Under the law, you are entitled to the information, and they cannot withhold it.

Keep an organized record of your requests. If the credit bureau is not responding to your 609 letter or any follow-up letters, you can report their behavior to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC).

Keep an organized record of your requests. If the credit bureau is not responding to your 609 letter or any follow-up letters, you can report their behavior to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC).This is the federal agency charged with enforcing the FCRA. Filing a complaint with the FTC will put additional pressure on the credit bureau to respond and also to fix any errors in your credit report.

Even though it's probably understood, it might still be worth mentioning. Submitting a 609 dispute letter isn't about finding a clever legal loophole. It's just about making sure your rights are protected and taken care of under the law.

And that's worth a whole lot.

Still have questions? We've got the answers! Let us know in the comment section below, and we'll be sure to respond to you.

If you haven't heard the term "tradelines" before, sit back, grab a cup of coffee and let me tell you precisely what they are, how they work, how you can use them, and whether doing so is legal.

The simplest way to explain a tradeline is:

It is a record of activity for any type of credit extended to a borrower and reported to a credit reporting agency. Tradelines are created on a borrower's credit report to track all the account activity. A tradeline is established for every line of credit or debtor's account, such as a mortgage, car loan, student loan, credit card, or personal loan.

It is a record of activity for any type of credit extended to a borrower and reported to a credit reporting agency. Tradelines are created on a borrower's credit report to track all the account activity. A tradeline is established for every line of credit or debtor's account, such as a mortgage, car loan, student loan, credit card, or personal loan.Basically, a tradeline is a record-keeping mechanism that tracks the activity of borrowers on their credit reports. Each and every credit account has its own tradeline.

Borrowers can, and usually do, have multiple tradelines on their credit reports. Each one represents the individual borrowing accounts for which they've been approved.

That's the long and short of what a tradeline is and why we have them. So far, they don't sound that complicated or important, right?

Tradelines can contain different data points that give information about the creditor, the lender, and the type of credit being provided. Things like:

It starts to get interesting when you learn that the information included in your tradelines is used to calculate your credit scores. And that's really where your ears should perk up and dial in.

Your credit score is a summarized snapshot of your creditworthiness, used to determine whether lenders will be willing to lend to you. Factors considered include how many tradelines you have and the types and lengths you've had, good or bad. New tradelines can be used to influence and boost your score.

Your credit score is a summarized snapshot of your creditworthiness, used to determine whether lenders will be willing to lend to you. Factors considered include how many tradelines you have and the types and lengths you've had, good or bad. New tradelines can be used to influence and boost your score.

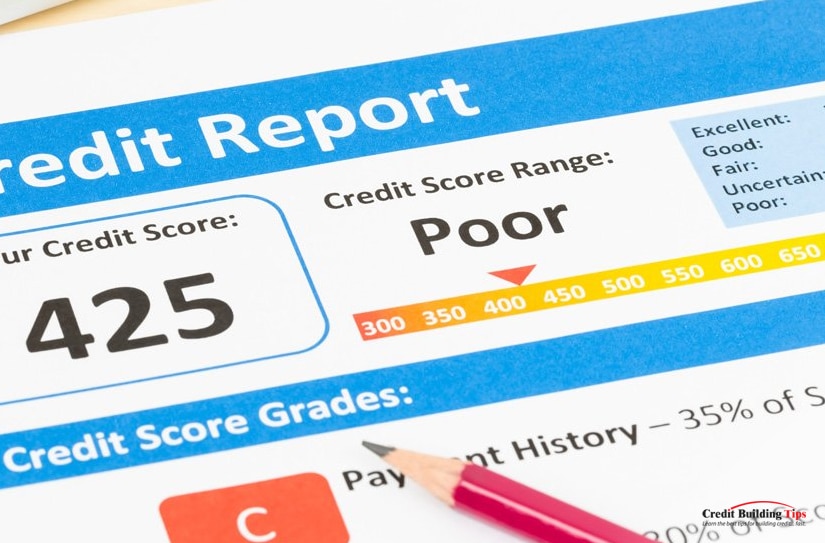

A good credit score gives you access to reasonable interest rates, faster loan approvals, and suitable insurance policies. Unfortunately, nearly 70 million Americans suffer from bad credit because fixing your credit score takes time and self-control.

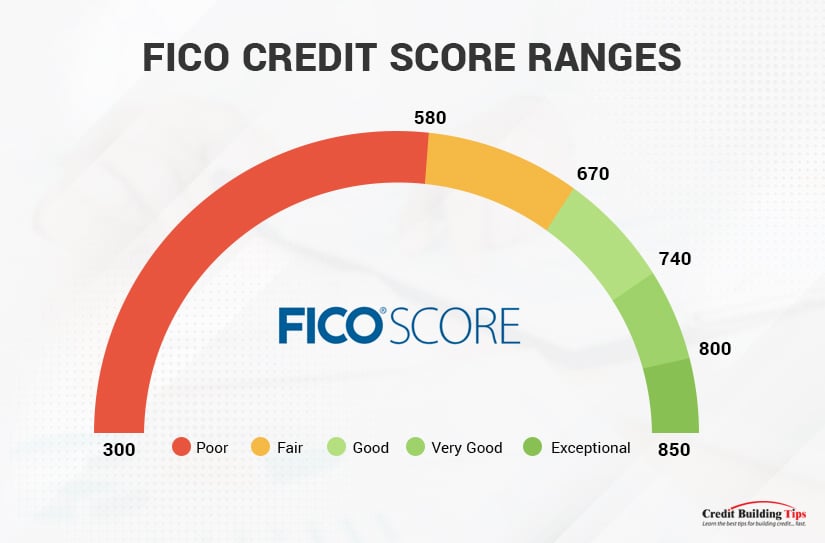

When you apply for credit, your lender will want to "pull" your credit score as part of their approval process. Your FICO score is made from the information listed on each trade line associated with your name.

These scores are calculated using many different pieces of credit data in your credit report.

The data is grouped into five categories, each with a pre-determined percentage of weight given:

A fairly recent addition to calculating your credit trustworthiness is a predictive score that looks at how likely you'll go bankrupt in the next two years. This is called a Bankruptcy Navigator Index (BNI), and this number might be the reason you're turned down for a loan or mortgage, even if your FICO score is healthy.

A fairly recent addition to calculating your credit trustworthiness is a predictive score that looks at how likely you'll go bankrupt in the next two years. This is called a Bankruptcy Navigator Index (BNI), and this number might be the reason you're turned down for a loan or mortgage, even if your FICO score is healthy.You can't look at your BNI as it's not included in your credit report. The BNI was developed by Equifax and is an internal score that is only available to lenders.

Equifax describes the difference between consumers who have bad credit and one who they feel are facing bankruptcy in the next 24 months as:

"Delinquent consumers have moderate financial difficulty, which is often a long-term chronic behavior. They manage credit poorly and occasionally miss payments, sometimes with multiple missed payments leaving to collection efforts and write-offs.

Consumers heading into bankruptcy are in severe financial difficulty. They make smaller payments on their credit cards. They tap into their line of credit to make their installment loan payments. They shop for additional credit cards, a new line of credit, and consolidation loans.

Eventually, they reach their limit on their cards and lines of credit. They are forced to declare bankruptcy; however, their delinquency score remains satisfactory because they have not missed payments."

So, if you have poor or even worse credit, obviously, you'll want to find ways to boost your credit score.

You should review your credit report:

Because your score changes as your accounts change, it's important to keep an eye on your tradelines.

There's an important distinction between two types of tradelines: primary and authorized user tradelines. When you personally open an account, you have a primary tradeline. When you are added to someone else's account, you're an authorized user of that tradeline.

Adding primary tradelines to your credit report and keeping these lines of credit healthy is the best way to build a credit history and boost your credit rating. As the only responsible party, you must make at least minimum payments for every cycle where repayment is due.

But here's the catch. Suppose you don't have proof that you would be a reliable borrower. In that case, it's almost impossible for lenders to view you as responsible, and it becomes hard to qualify for free primary tradelines.

But don't despair. If you're one of the 70 million Americans who suffer from bad credit, there is a way to improve your credit score. Get more tradelines and keep them healthy.

Let me be clear here. I'm not suggesting you get more tradelines and neglect repaying the amounts owed. I'm suggesting (and assuming) you want to repair or start building your credit rating and could use a lift on doing so more quickly than just killing yourself to pay off your loans.

Let me be clear here. I'm not suggesting you get more tradelines and neglect repaying the amounts owed. I'm suggesting (and assuming) you want to repair or start building your credit rating and could use a lift on doing so more quickly than just killing yourself to pay off your loans.Depending on how deeply you are buried in debt, it could take years to repair your credit score. In the meantime, you won't have access to reasonable interest rates, faster loan approvals, and suitable insurance policies.

Once you learn your FICO credit score, you can see which one of the five grades your score would give you:

Getting two or three "seasoned" tradelines can help you jump to a higher credit score in a month if your credit score is less than ideal.

Having good tradelines on your account can improve your rating within 25-30 days.

The first and most important thing to remember when you're looking to buy primary tradelines is to make sure you buy from reputable tradeline companies. Credit Repair Expert lists the five best tradeline companies of 2022 in one of their recent blog posts and writes extensively on how they compare to each other.

Any reputable tradeline company should have these qualities:

If they don't tick off all the boxes on the list above, stay away from them!

While buying primary tradelines is a great way to improve your credit score quickly, it doesn't come without drawbacks.

Don't buy accounts that are in default. Even though by turning over the account to a collection agency, the lender lets the account become available to transfer to a new owner, buying a tradeline with a bad history is not helpful.

Don't buy accounts that are in default. Even though by turning over the account to a collection agency, the lender lets the account become available to transfer to a new owner, buying a tradeline with a bad history is not helpful.

Be cautious about opening a line of credit with a particular store or business to improve your credit score. While it's perfectly safe and legal to do this, you'll usually have to pay sizeable annual fees, and your credit score could take a temporary hit for opening an account.

Be cautious about opening a line of credit with a particular store or business to improve your credit score. While it's perfectly safe and legal to do this, you'll usually have to pay sizeable annual fees, and your credit score could take a temporary hit for opening an account.Even more important to consider is if the account only works at one specific business, will you actually make regular purchases there? If you don't and your card sits at a zero balance, you're damaging your score as a credit agency views this as an inactive account.

If you find buying fast, safe, and price-conscious primary tradelines tough, you may want to look at authorized user tradelines. They're basically a way to rent a primary user's credit history. Doing this can let you up your credit score in a short amount of time.

Not only are you renting the ability to buy things on credit, but you are also renting the previous payment history and account characteristics.

While there's some controversy about whether buying primary or authorized user tradelines is better, Mike at Superior Tradelines makes a compelling case for why buying authorized user tradelines is better.

He describes buying seasoned tradelines as being a legal credit hack. But one that only works well when used correctly.

Opening a joint account (piggybacking) is probably the best way to add authorized user tradelines to your credit report. This became legal between family members when the ECOA was passed.

But not everyone has a family member with good credit or the willingness to share their credit with them. That's when the federal government stepped in to allow non-family members to piggyback on a primary user's account as long as they had permission to do so.

If you start to look more closely at the idea of using tradelines, you'll often come across the term "seasoned" tradelines. This term refers to the age of the tradeline.

How long you've had the tradeline — the credit account age — is used to grade your credit score. It takes two or more years for a tradeline to mature enough to be called "seasoned." That may be longer than you have to wait.

That's why buying seasoned tradelines is more valuable than getting your hands on "immature" tradelines.

You can either buy authorized user tradelines or share a family member or friend's good credit. Of course, both ways have pros and cons, but in the end, I recommend you buy them from a trusted professional.

Although you'll pay for the privilege of buying an authorized user tradeline, the peace of mind you get from dealing with a company with the experience of knowing what you need and how to help you get it is immeasurable.

Not to mention, dealing with a professional eliminates any potential risk to your family and friend relationship. No good credit is worth it if the cost is the relationship of your closest support network.

Protect yourself by doing your homework on the company you are considering buying from. You want to look for a professional and legitimate company that is:

Here's what the heavy hitter, The Finance and Economics Discussion Series, Division of Research & Statistics and Monetary Affairs from the Federal Reserve Board in Washington, D.C. has to say about authorized user tradelines:

"...these numbers appear to indicate that the practice of piggybacking credit can increase credit scores to an economically significant extent if the account to which a nonprime borrower is being added is of sufficiently high quality. Furthermore, it appears that a large fraction of borrowers, particularly borrowers with thin or short credit histories, can obtain substantially higher credit scores as a result of this practice. This suggests that the practice of piggybacking credit offers the substantial potential to increase the credit scores of individuals added as authorized users on existing accounts and consequently to enhance their access to credit at lower costs."

Ultimately, having good credit comes from making more than you spend and not spending what you don't have. Paying your bills on time and not allowing your debt to others to rack up are all ways you can control your credit rating and be someone who lenders will look at favorably.

Ultimately, having good credit comes from making more than you spend and not spending what you don't have. Paying your bills on time and not allowing your debt to others to rack up are all ways you can control your credit rating and be someone who lenders will look at favorably.And in the meantime, if you need to do some repair work, consider how tradelines can help you get back on track.

Whenever you have a debt that you cannot pay, that debt has a chance of being sent to collections.

Being "sent to collections" isn't quite the formalized process it sounds like, though. Collections agencies, or debt collectors, are simply companies that buy debt from entities like healthcare facilities, banks, and landlords. Unsecured debt (that is, debt that isn't attached to an asset that can be repossessed) can be purchased by these companies.

These companies buy debt for pennies on the dollar. A bank or other entity is willing to take this deal because getting some small percentage of the money is better than spending their own money trying in vain to recover the money from you. The debt collector does that as their sole job; a hospital might not even have people who have the time to try it.

That's also how debt collectors make their money: since they bought your debt for 2% of its value, they can recover the full value – or even accept less than full value – and still make a profit.

Debt collectors are often quite difficult to handle. Throughout history, they've been anything from purely business to "hunt you down and break your legs" levels of dangerous. Modern debt collectors, thankfully, have to obey a ton of different laws that regulate their behavior.

Debt collectors are often quite difficult to handle. Throughout history, they've been anything from purely business to "hunt you down and break your legs" levels of dangerous. Modern debt collectors, thankfully, have to obey a ton of different laws that regulate their behavior.Let's get started!

Debt collectors use a lot of different methods to try to get money from you to repay your debts.

For example:

Obviously, an unpaid debt on your credit report is bad. Even if you pay it, the blemish lasts up to seven years before it falls off of your report. That's a lot of long-term damage for something that may have been as minimal as a temporary financial hardship.

Did you know, though, that there's no actual rule that requires debt collectors to report debts to the credit bureaus? Most will do it as a form of threat to get paid, but it's not legally required of them.

That's where a "pay for delete" comes into play. What is it, though?

A "pay for delete" is a form of negotiation with a debt collector. It's an offer: if you repay the debt, either in full or as an agreed-upon partial payment, the debt collector will wipe the slate clean and cease reporting the debt to the credit bureaus. The blemish is removed from your credit report, so your score goes up, and you don't have to suffer seven years of hardship over a bit of bad luck.

A "pay for delete" is a form of negotiation with a debt collector. It's an offer: if you repay the debt, either in full or as an agreed-upon partial payment, the debt collector will wipe the slate clean and cease reporting the debt to the credit bureaus. The blemish is removed from your credit report, so your score goes up, and you don't have to suffer seven years of hardship over a bit of bad luck.Sounds like a winning offer, right? If you can afford to pay off the debt, having it wiped from your credit report is great for your future financial stability.

Unfortunately, there are a few problems with this practice.

The first issue is that, while a pay for delete could potentially remove the blemish caused by the debt collector, that's all it does.

If you had a credit card bill go into collections and linger delinquent long enough that it's sold to debt collectors, that's a blemish on your credit report, reported by the credit card company. Nothing you can do can remove that blemish other than waiting the requisite seven years.

The debt collector's reporting adds a second blemish that can be removed, but that doesn't remove the original blemish.

While we hesitate to say that a pay for delete is illegal, it can be said that they aren't entirely above-board. However, it's not your problem; it's the problem of the credit reporting agencies.

Under the Fair Credit Reporting Act, the credit reporting bureaus are required to report accurate information about your credit. They cannot use an excuse like "we're just reporting information we're given" and wash their hands of any problems.

Picture this: someone is applying for a credit card. You're responsible for reviewing their credit history, and while it has a couple of blemishes, they have no recent collections accounts, so you approve them.

That individual actually just recently had an account in collections, but they negotiated a pay for delete, so it wasn't on their report. Now, you've approved a credit card for someone who has a much greater level of risk than you would normally approve. All because their credit report was inaccurate.

That's the tricky situation that various financial institutions and credit bureaus are put in when a pay for delete comes through. It's a gray area; while the credit bureaus shouldn't report things that aren't verified with them, they also shouldn't "sculpt" a credit report in such a way either.

That's the tricky situation that various financial institutions and credit bureaus are put in when a pay for delete comes through. It's a gray area; while the credit bureaus shouldn't report things that aren't verified with them, they also shouldn't "sculpt" a credit report in such a way either.One of the biggest problems with a pay for delete is that a debt collector can happily agree to it and then, once you've paid the debt, simply not remove the blemish at all.

Since pay for delete agreements aren't formalized contracts, they aren't a legally-recognized process, and they go against accurate credit reporting rules, you're left without recourse. You can't really sue a debt collector for accurately reporting your credit information and not upholding their end of an unenforceable bargain.

All of this means that a pay for delete isn't really a valuable process these days.

There's one other quirk of the credit reporting system that makes a pay for delete an even less valuable process to try: it doesn't matter in the first place.

Above, we mentioned that a debt collector typically ends up adding a second blemish to your credit report attached to the same debt. In fact, if you ignore a debt collector long enough, they may even sell the debt to another collector, and it can change hands multiple times: the same debt could end up with several entries in your credit report.

In the past, this was devastating. Pay for deletes were often seen as one of the only ways to handle such a situation.

Today, even if you get a pay for delete, the original debt going to collections is still reported, and you'll never get a bank, landlord, or other entity to agree to a pay for delete for a debt they no longer own.

Today, even if you get a pay for delete, the original debt going to collections is still reported, and you'll never get a bank, landlord, or other entity to agree to a pay for delete for a debt they no longer own.

There's one major reason why this isn't a huge problem, however: modern credit scores take it into account.

Or, more specifically, they don't take it into account.

Specifically, the newest version of FICO, FICO 9, and the latest VantageScore 3 both simply ignore most debt collectors… if the account is paid.

Essentially, a pay for delete is built into the credit reporting system now. You don't need to negotiate one because it's simply the default behavior.

There's one caveat, however. That is, it only applies to the latest credit scoring models. There are plenty of agencies out there, like mortgage lenders, who still use older versions of FICO like FICO 8 instead of FICO 9, and as such, still see the hit to your credit that a paid collections account gets you.

There's one caveat, however. That is, it only applies to the latest credit scoring models. There are plenty of agencies out there, like mortgage lenders, who still use older versions of FICO like FICO 8 instead of FICO 9, and as such, still see the hit to your credit that a paid collections account gets you.That's why we can't simply put the concept of a pay for delete behind us; we need to wait for the whole financial industry to catch up.

Yes and no.

Right now, a pay for delete may be able to raise your credit score slightly. It cannot fully remove the blemish caused by an unpaid debt since the original creditor will still be listed with a debt that was sent to collections. However, knock-on debts from collectors can be removed.

While modern scoring doesn't much care about paid collections accounts, if you're specifically seeking a mortgage, car loan, or other financing, it might still be relevant.

However, a pay for delete is somewhat risky in that while you can negotiate the agreement, it's not legally binding, and the debt collector doesn't actually have to honor the agreement. Since all they care about is getting money out of you, they'll often promise anything they feel like if it gets you to pay, with no intention of upholding it.

So, while you can negotiate a pay for delete, the more important part is negotiating a settlement. A pay for delete is often an agreement to pay a partial sum of the debt in order to call the debt cleared; if the debt collector agrees to it, you've essentially negotiated a partial payment. Of course, every step of the process should be documented in writing in case someone else tries to collect on the same debt later.

Rather than simply jumping to a pay for delete offer, there's a whole process to follow to handle an account in collections.

The first thing to do is send a letter requesting verification of the debt. A debt validation letter is a request to the debt collector, requiring them to prove that the debt is legitimate and that you owe the amount stated. Under the Fair Credit Reporting Act and the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act, you're legally protected if a debt collector can't validate a debt.

Specifically, look for errors or misreporting. For example, if you paid a credit card bill, but the bank misapplied the payment and eventually sent the account into collections, you may be able to prove that you paid the debt and that it's a bank error. Similarly, medical accounts that should have been covered by insurance but slipped through the cracks can also cause these issues. If you can verify that you're not responsible for the debt, they can't collect on it.

If your debt is truly in error, you can file a dispute with the credit bureaus. If you can prove that you aren't responsible for the debt, it can be wiped from your credit report as part of the fair credit reporting standards. Accuracy goes both ways, after all.

If a debt collector is overly aggressive or violates rules about debt collection practices, you can file a complaint against them. The Fair Debt Collection Practices Act specifies conduct for debt collectors, including what hours of the day they can call, what information they can and cannot provide, and more. If they violate these rules, they can be subject to fines, lawsuits, and other penalties.

If the debt is yours, it's validated, and it's accurate; it's your responsibility to pay. However, you may be able to negotiate a settlement and pay a partial value to wipe the slate clean. Debt collectors are often more than happy to accept a partial payment, though some will not; it all depends on the collector specifically.

If all else fails and you have no way of repaying a debt, you can also simply ignore it. The blemish will linger on your credit report for seven years, and that's detrimental to your credit, but it will eventually fall off of your report. It's not the ideal option, but it's the final option.

Dealing with debt collectors is stressful enough. A pay for delete may not be worth the effort, especially when modern credit scores don't count paid accounts anyway. Depending on your circumstances, it may be a useful technique, but it's often just easier to pay the debt without all the paperwork and negotiation.

There are a few kinds of unexpected expenses that are common in America, but few are as prevalent and as devastating as medical bills. The healthcare system is a mess, with a gigantic feedback loop between hospitals and providers, third-party labs, insurance companies, and reimbursement programs, all trying to raise numbers to get their own cut and remain solvent. Prices are constantly rising to compensate for the rise in other prices, deferring costs on and on until it all ends up with a bill with a few too many zeroes arriving in your mailbox.

Unfortunately, medical debt is extremely common. High prices make it hard for the average person to even consider paying a massive medical bill, and it's often much easier to default and ignore it than to labor for years or decades struggling to pay it off.

Unfortunately, medical debt is extremely common. High prices make it hard for the average person to even consider paying a massive medical bill, and it's often much easier to default and ignore it than to labor for years or decades struggling to pay it off.If you have medical debt, can you dispute it? If it goes to collections, are you on the hook? Or can you get out from under it?

Here are some of the most commonly asked questions and answers!

First, let's get the first question out of the way. Are you on the hook for medical bills you receive for services rendered?

The answer is yes, but also no. Usually, you are on the hook for medical bills you receive, with one major caveat: only if those medical bills are accurate.

The answer is yes, but also no. Usually, you are on the hook for medical bills you receive, with one major caveat: only if those medical bills are accurate.The healthcare system is massively complicated, with dozens of organizations butting in, from insurance to labs to providers to facilities.

There are a ton of opportunities for paperwork, authorization, and information to get lost along the way. So much so that it's extremely common to receive bills for services that should have been covered by insurance simply because the facility billing you never received your insurance authorization.

If you've received an unexpected medical bill in the mail, you'll want to follow a process to verify it before you pay.

First of all, look at the bill and make sure it's relevant to the procedures you actually received. Medical billing is often handled by numerical codes identifying various procedures, from a simple X-ray or an antibiotic prescription all the way to major surgeries. It's extremely easy for a typo to make its way into the system, whereupon your insurance rejects a claim for a procedure it didn't authorize, and you receive a bill.

You'll also want to check any records of the procedures you actually received. It's possible in some instances that you may have received certain kinds of treatment, and you didn't really understand what was happening, or you may have been unconscious when they had to perform the procedure. Many small details can slip through the cracks.

Also, check your explanation of benefits statement. This statement should come from your insurance company and explains what they cover and what they don't. Make sure coverage is applied properly; sometimes insurance authorization isn't properly used, and sometimes something that should have been covered actually isn't.

Another question you may have is whether or not the facility or practitioner's office can help you or if you're stuck trying to negotiate with insurance companies.

As long as the bill is active – that is, it hasn't been sold to debt collectors – you can keep the facility in the loop.

As long as the bill is active – that is, it hasn't been sold to debt collectors – you can keep the facility in the loop.You often have many options, in fact:

If you can't pay an even discounted version of your bill, you can discuss payment plans, but you may also want to put that off in favor of other discussions.

Another call you'll want to make is to your insurance company. Your insurance company may actually be obligated to cover a bill you received, especially if they were supposed to but never received the claim themselves.

Another common issue is double billing, where the bill is processed normally, insurance pays it, but somehow a duplicate bill is created and sent to you. In these cases, the hospital has already been paid, and you aren't beholden to pay it again. This is very common with certain third-party labs for blood tests and biopsies, for example.

If a claim was made with your insurance and it was denied, you may also be able to file an appeal. Unfortunately, insurance companies are quite adversarial, so they'll likely fight if they can.

The American healthcare system is massively exploitative, but there are some legal restrictions in place. In particular, there are two you'll want to learn.

The first is the Fair Credit Reporting Act. This Act requires that anyone who wants to collect on a debt from you must be able to prove that the debt is legitimate. For a healthcare provider or facility, that means verifying the bill and each line item on it. If they can't prove that you received the care they're billing you for, they can't bill you for it. This even applies if you did receive it, but they didn't keep records, though that's exceedingly rare.

The first is the Fair Credit Reporting Act. This Act requires that anyone who wants to collect on a debt from you must be able to prove that the debt is legitimate. For a healthcare provider or facility, that means verifying the bill and each line item on it. If they can't prove that you received the care they're billing you for, they can't bill you for it. This even applies if you did receive it, but they didn't keep records, though that's exceedingly rare.For debt collectors, who are third parties who buy up the debt from hospitals, it's even more important to verify the debt. The transition from hospital to debt collector is a prime opportunity for mistakes or for lost paperwork, and if the debt collector can't verify the debt, they can't charge you for it.

The FCRA also limits how debt collectors can contact you and limits "coercive credit reporting," where a debt collector threatens to report to the credit bureaus if you don't pay right away.

It's also worth knowing that credit bureaus treat medical debt less harshly than other forms of debt. From Experian:

"FICO 9, the most recent FICO credit scoring model, as well as the VantageScore® 3.0 and 4.0 credit scoring models, don't weigh medical collections as heavily as other collections. Additionally, the three major credit bureaus (Experian, TransUnion, and Equifax) will remove the collection account from your credit history if it's been paid."

Additionally:

"Not every medical collection will be included on your credit report. The three major credit bureaus wait 365 days before adding medical collections to your credit history. The purpose of this yearlong grace period is to give you a sufficient amount of time to resolve any errors on your bill, pay your bill, design a payment plan or consult your insurance company so they can take care of it."

What this all means is that medical debt is generally among the least impactful forms of debt when it comes to your credit report. It can still bring your score down, but it won't be as much of a decrease as a similarly-sized personal loan or a defaulted mortgage, and it goes away much more easily than other forms of debt.

The other, implemented as of January 1, 2022, is the No Surprises Act. This is another Act that implements protections, specifically for medical bills.

The other, implemented as of January 1, 2022, is the No Surprises Act. This is another Act that implements protections, specifically for medical bills.In particular, one of the common sources of high bills was when a facility like a hospital is in-network for your insurance, but the doctor who actually saw you is a contractor from a private practice that is out of network. Thus, you're billed out-of-network rates instead of in-network rates. Obviously, this is terrible for the consumer. The No Surprises Act prohibits this practice and puts limits on how much you can be billed.

As mentioned above, yes, you can. If a medical bill goes unpaid and is sent to a debt collector, you can dispute it by requesting verification before you pay.

As mentioned above, yes, you can. If a medical bill goes unpaid and is sent to a debt collector, you can dispute it by requesting verification before you pay.Furthermore, if a medical bill is sent to the credit reporting agencies, you can dispute the entry on your credit report. The credit bureaus will also ask for verification of the debt, and if they do not receive it, they will remove the debt from your credit report.

Another option you can consider is what's called a Pay For Delete.

If a debt is reported to your credit report, you can contact the agency that reported it and ask if you can negotiate a pay for delete. The agency – usually a debt collector – may be willing to play ball. A Pay For Delete is when you agree to pay some portion of your debt in exchange for them removing it from your credit report. You can read more about it here.

If a debt is reported to your credit report, you can contact the agency that reported it and ask if you can negotiate a pay for delete. The agency – usually a debt collector – may be willing to play ball. A Pay For Delete is when you agree to pay some portion of your debt in exchange for them removing it from your credit report. You can read more about it here.Truthfully, you probably don't need to worry about a Pay For Delete, as the behavior is now the default. When you pay off a collections account, that account is removed from your credit report.

Yes. If contacting the hospital for verification and negotiation hasn't helped, and insurance is stonewalling you, you have a few other options you may be able to ask for counsel.

Yes. If contacting the hospital for verification and negotiation hasn't helped, and insurance is stonewalling you, you have a few other options you may be able to ask for counsel.First is a patient advocate. Patient advocates are generally employees of the healthcare provider, and their job is to fight on your behalf and see what strings they can pull to reduce or remove your financial obligations. It's also possible that your insurance company has patient advocates as well.

The second option is your state's insurance commissioner. This is most relevant if your insurance company is refusing to cover something they should. The insurance commissioner should be able to help you navigate your situation and can verify that the insurance company is or isn't doing everything right, with penalties if they're trying to do something wrong.

Some states, like California, also have processes like an Independent Medical Review, which uses a third-party investigator to handle the verification and validation of services, billing, and other aspects of the process.

A third option, and usually your last resort, is a lawyer. Legal counsel can advise you on steps you can take and the options you have. Unfortunately, lawyers are often expensive themselves, so even if you get a medical bill removed, you may end up owing the lawyer almost as much.

Bankruptcy is a legitimate process, and as unsecured debt, medical debt can be discharged. After all, it's not like a hospital can repossess your health!

That said, bankruptcy is harsher on your credit score and lingers longer than medical debt, so this should be an option of last resort. Additionally, there's no such thing as "medical bankruptcy"; you cannot declare bankruptcy just from your medical debt; it's an all-or-nothing process. Don't take this step lightly, but keep it in mind as the ultimate out.

If you've received a medical bill and you don't think you should have, follow this process.

1. Contact your healthcare provider and ask for an itemized bill.

2. Compare the itemized bill with the explanation of benefits from your insurance company, looking for errors.

3. Examine your insurance policy for limits, maximums, coverage details, and other processes that may be used to cover the bills you receive.

4. Dispute any errors you find, either with the insurance company or the healthcare provider.

5. Consider a payment plan. If your bill is legitimate but just hard to pay, you can often negotiate with the provider to pay a portion of it or establish a payment plan. Facilities are often much happier with partial payments than they are with no payments at all.

6. Monitor your credit report in case a bill slips through and defaults or is sent to collections.

7. Dispute any errors or issues with your credit report.

8. Dispute any medical debt that has been sent to collections.

9. Consider contacting various forms of assistance, like a patient advocate, state insurance commissioner, or lawyer.

Throughout this entire process, the #1 thing you should be doing is documenting everything. Save all paperwork and communications, request letters rather than phone calls and verbal agreements, and get things in writing. The paper trail is hugely helpful if you end up in a situation where you need to pursue legal action, though 99% of the time, you won't.

Repossession is a worst-case scenario, given an even worse reputation through its use as a pop culture signifier of failure and hard times. Yet it's something that can happen to anyone in the wrong circumstances.

If you're facing repossession or worried you could if you take on a bit more of a car loan than you should, you're probably wondering what kinds of repercussions it can have on your credit.

So, let's talk about it!

When you buy a car, unless you're paying for it in cash, you're probably financing it.

Financing a car means taking out a loan, either through your own bank or through a bank affiliated with the dealer. The loan is the financial institution giving you the money to pay for the car from the dealer. When you drive off the lot, the dealer can wash their hands of the situation; it's now just between you and the bank.

In order to guarantee that they get their money in some form or another, the bank maintains a form of security: the title to the car. As long as you haven't fully paid off the loan, technically, you don't own the car: the bank does. You're simply allowed to use it until you've fully paid it off, at which point the title is mailed to you, and the car is fully yours.

What happens if you stop making payments on the car? Well, that's when repossession comes in. First, though, you enter late payment status. During late payment status, your account falls past due, and you're given the opportunity to pay up and make things right.

In many cases, especially if it's your first missed payment, your bank will cut you some slack. They don't want to leap to penalties right away since that disincentivizes you from trying to make further payments. You can pay up with no further penalties, or you can try to negotiate new terms for lower ongoing monthly payments (usually for longer periods.)

If you continue to not pay, then your loan enters default status. When a loan has defaulted, the lender can take action to try to recover their losses.

If the loan is unsecured (such as medical debt, student loans, or credit card balances), the lender will need to take you to court to recover their money. They can't repossess your education or your health, after all. Instead, they'll ask the court for a judgment, which can result in garnished wages or other liquidated assets.

Car loans are secured loans, however. Secured means that the bank maintains the asset ownership and can take it back if you don't finish paying for it. Hence, repossession; if you haven't finished paying for the car, you still don't own it, and they can still take it back.

Car loans are secured loans, however. Secured means that the bank maintains the asset ownership and can take it back if you don't finish paying for it. Hence, repossession; if you haven't finished paying for the car, you still don't own it, and they can still take it back.Typically, lenders won't start repossession proceedings until your payments are at least 60 days late. Even then, there's often a grace period to work with to try to get back on track or negotiate new terms. Repossession terms are also governed by state law, and the lender may need to deliver you notice in advance of their intent to repossess your vehicle.

As an additional note, the lender can't damage the vehicle to take it (like breaking a window to access it), and they can't steal your personal property from inside it; you're entitled to anything you left in the vehicle.

When a bank repossesses a vehicle, they generally will try to sell it and apply the funds to pay the remaining balance of the loan. In the exceedingly rare instance where the car sells for more than you owed on the loan, you're entitled to the surplus; conversely, if the car sells for too little to cover the balance, you'll still owe the remaining amount.

So, here's a question. If you're familiar with how credit works, you know that defaulting on a loan, or even missing payments enough that you run out your grace period, will hurt your credit score. So, does having a vehicle repossessed hurt your credit too, or is the damage just from defaulting on your loan?

The answer is both yes and no.

When an asset is repossessed due to a loan default, the repossession will be noted on your credit report. However, that in and of itself isn't necessarily mathematically calculated into your score. More often, it's more like a "soft" factor. The real damage comes from late payments, missed payments, defaults, and any court judgments that are also noted on your credit report.

When an asset is repossessed due to a loan default, the repossession will be noted on your credit report. However, that in and of itself isn't necessarily mathematically calculated into your score. More often, it's more like a "soft" factor. The real damage comes from late payments, missed payments, defaults, and any court judgments that are also noted on your credit report.Truthfully, it doesn't really matter. A repossession is inextricably linked to the other dings on your credit report, and there's not really a way to separate the two. Your car won't be repossessed unless you've fallen off your loan payments, and you won't get a repossession on your credit report without those blemishes already being there.

So, your credit will start being hit before repossession is reached and will still be damaged afterward.

A repossession and all of the associated damage can tank your credit score by as much as 150 points (if it's relatively high to start) or something closer to 50 (if your score is only fair or lower.) It's a significant hit that lingers for nearly a decade, so it's better to do what you can to handle it before it reaches that point.

Car loans are among the largest single purchases many people ever make (second only to houses in many cases), so they have a serious impact on your credit.

Much like just about everything else on your credit report, a repossession will linger for seven years.

Much like just about everything else on your credit report, a repossession will linger for seven years.There are ways to try to get it removed earlier, but they're inconsistent and generally aren't applicable unless you are able to recover your car before it is sold off and repay your loan.

If you are able to negotiate and pay off your loan after falling into default, you may be able to get a repossession removed from your credit report early. You likely won't be able to completely remove every blemish, but some of them can be erased in the right circumstances.

Generally, there are only three ways for a repossession to be removed from your credit report.

It's generally a bad idea to file a dispute over something that is accurate in the hopes that a paperwork error works out in your favor. It burns bridges and can make future disputes more difficult, even if they're more warranted.

Sometimes, if you fear falling into default and your car being repossessed, you may participate in a voluntary repossession. A voluntary repossession is when you willingly return the vehicle to the lender instead of waiting until they're forced to get it.

A voluntary repossession is still a repossession, however, and it still affects your credit in the same way. It may save you a small amount of money (the lender doesn't have to get the vehicle towed and stored, which are fees they pass on to you), and it can save you stress emotionally, but it's still not great.

The best it can do, really, is build a bit of good grace with your lender; you're working with them, not fighting them, and that counts for something.

The best it can do, really, is build a bit of good grace with your lender; you're working with them, not fighting them, and that counts for something.

A better solution is generally to try to sell the car instead. If you can sell the car privately for more than the lender would auction it for, you can apply that money towards paying off the loan. It still leaves you without a car – and maybe some outstanding loan balance – but it's better than a full repossession. Unfortunately, it's not always possible; the bank may not be willing to sign over the title to someone else when you haven't paid it off.

If you're worried about your car being repossessed, you may be able to take steps to mitigate the problem before it comes to that point.

First, analyze your situation and see if you can isolate a particular reason for your financial hardship. Sometimes, a tough but doable action (like cutting out a vice or habit) can save you enough money to rebalance your finances.

Sometimes it's obvious; a lost job, a medical issue, unexpected hardship, and other problems can lead to cascading failure.

In these cases, you should do what you can to negotiate with every source of bills you have.

There are many programs available to help people buy some time to recover from health problems or find a new job. Taking advantage of them is stressful in its own way, but it's better than resisting assistance and falling even more behind.

You can also consider informal and temporary solutions, such as asking friends and family for help, setting up a GoFundMe, or selling off other assets to handle immediate obligations. It's not always possible, of course, but many people have more leeway than they think they do if they look for it.

Repossession is generally a last resort for everyone involved. Lenders know that, without a vehicle, it becomes exponentially harder for you to recover and repay your obligations. They also know that repossessing and selling a vehicle is expensive, time-consuming, and unlikely to fulfill the full value of a loan. As such, they tend to be willing to cut you slack or take actions that can give you more leeway if you ask.

If you ever have any further questions credit-related, whether about building credit, fixing credit, or similar, please do not hesitate to reach out and contact us! We'll gladly answer any of your potential questions, and would love to assist you however possible!

Bankruptcy is one of those processes that is rife with misinformation, misconceptions, and fear. It's a process you only ever encounter if you're in a bad position in the first place, and you're not in the right mindset or circumstances to fully understand what's going on. After all, the top causes of bankruptcy are:

All of which put significant strain on your emotions, cognitive processing ability, and stable living environment. If you're sick, if you're processing a devastating emotional change, or you've lost a job and are suffering the repercussions (or if you're dealing with any of those and putting the problem on a credit card), you're going to be in a bad place when it comes to learning about bankruptcy.

The truth is, bankruptcy isn't always as bad or as scary as many people make it out to be. That's why we're here; to help explain things in simple terms and guide you towards a positive solution.

The truth is, bankruptcy isn't always as bad or as scary as many people make it out to be. That's why we're here; to help explain things in simple terms and guide you towards a positive solution.Bankruptcy, as with any major financial change, has repercussions on your credit score. The question is, what are they, and how can you recover if you need to? Let's go through the most common questions people ask about the bankruptcy process.

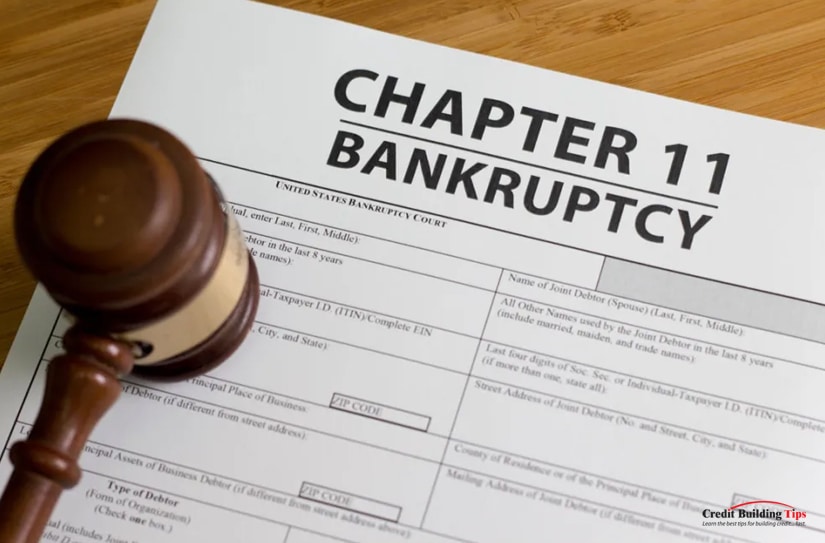

You may have heard of different kinds of bankruptcy, like chapter 11 or chapter 7.

All of them are basically the same event: you recognize that, in your current situation, you are unable to pay the debts you have accrued, whether those debts are medical expenses, credit balances, a mortgage, or something else.

When you come to this realization, rather than trying to run from the debts or ignore them, you go before a judge and admit that you're in a financially insolvent position.

The judge can then make a determination of what to do, and can wipe out your debts, wipe some of them, or establish a plan to repay them on more plausible terms. Everything else is details.

Bankruptcy is often viewed as a "fresh start" and a way to get out from under crushing debts. While this is somewhat true, there are a few debts that will not be erased with a bankruptcy.

These include:

Additionally, bankruptcy wipes away debt but does not do anything to the causes that put you in debt in the first place. If it was poor financial decisions and bad habits that got you in over your head, you need to adjust your lifestyle accordingly; otherwise, you'll end up in the same place again.

That said, some causes of bankruptcy, such as going underwater on a mortgage due to the financial crisis, are often temporary or one-time events.

You've probably heard of different kinds of bankruptcy, referred to as chapters. What does this mean?

"Chapter" simply refers to which section of the U.S. bankruptcy code governs the situation. Different chapters are used in different situations. There are actually six different chapters of bankruptcy, though 99.99% of the people reading this will only ever likely be subject to two of them. The six are:

This is the most common kind of bankruptcy for individuals. In it, you go before the courts and declare that you cannot pay your debts. A meeting of creditors is called wherein you are grilled about your assets and financial situation, and a determination is made about what debts cannot be removed, what debts you want to reaffirm (like a car loan, to keep your car), and what debts you need to be removed if possible.

At the same time, the judge will go over your existing assets and determine what you can keep and what you should sell to pay your debts. This can leave you with very little, though many states have specific laws about what you have to be allowed to keep (like basic shelter), and any debts left over are removed.

Chapter 7 bankruptcies stay on your credit report for 10 years, and you can't file for another one for 8 years.

Chapter 7 bankruptcies stay on your credit report for 10 years, and you can't file for another one for 8 years.The chapter 13 bankruptcy process reorganizes and restructures your debt, establishing two things: a strict budget you have to adhere to for your spending and a payment plan to repay the debts you can. It's very strict but allows you to keep your assets in general, rather than liquidating everything you have to pay your debts.

This kind of bankruptcy is the second-most common for individuals, stays on your credit report for 7 years, and has a 2-year "cooldown" before you can file for it again.

This kind of bankruptcy is the second-most common for individuals, stays on your credit report for 7 years, and has a 2-year "cooldown" before you can file for it again.Chapter 11 is common to hear about because it's the kind of bankruptcy that companies file to protect themselves from their bad decisions. Unless you're a business owner, you don't need to concern yourself with this chapter.

The remaining three chapters are specific kinds of bankruptcy for narrow groups of people. They are:

As you can see, there's a pretty low chance you'll have to deal with any of these, so we're not covering them in detail here. If you have a specific need to learn more, though, feel free to reach out or leave a comment, and we'll do our best to help. Remember, though; we aren't bankruptcy lawyers, so we can only offer so much guidance.

When you declare bankruptcy, as you might expect, your credit score will take a hit. It is one of the most significant detrimental hits you can take.

Remember, your credit score is a rating based on many factors, but it's aimed at telling creditors how well you can pay your debts. Declaring bankruptcy is a straight-up admission that you can't pay your debts. No matter how good your credit score was before your declaration, your credit score will take a huge hit.

Remember, your credit score is a rating based on many factors, but it's aimed at telling creditors how well you can pay your debts. Declaring bankruptcy is a straight-up admission that you can't pay your debts. No matter how good your credit score was before your declaration, your credit score will take a huge hit.

Various reports and records indicate that if your credit score is good – 700 or higher – declaring bankruptcy can cause it to drop by 200 points or more. That's a lot! If your credit score is lower, you'll see a drop of around 150 points. It's an extremely substantial hit, and since bankruptcies stay on your credit report for 7-10 years, that hit will follow you for a long time.

In truth, different kinds of bankruptcy can have different levels of impact on your credit report and score. This is because the determining factor is how able you are to pay back your debts. In a chapter 7 bankruptcy, you are paying little or nothing towards your debts, and most of your debts are wiped away. The creditors need to take that hit, and they hate doing that. So, a Chapter 7 bankruptcy is going to be worse.

Meanwhile, a Chapter 13 bankruptcy, while still devastating, isn't quite as bad. This is because the core of a Chapter 13 declaration is a reorganization of your finances, such that you can then pay what you can to furnish your debts. The impact on your credit will still be severe, but it won't be quite as severe as with a Chapter 7 declaration.

Let's say that, 7-10 years ago, you had severe unexpected medical issues and struggled to pay your medical debts. Disregarding commentary about the absolute failure of the medical system to allow this, you end up needing to declare bankruptcy to get out from under those crushing debts. Since then, you've spent time recovering, both physically and financially. What happens to your credit score?

Well, assuming you haven't fallen into old habits and racked up even more debt you can't pay, chances are that your credit score has slowly been improving over the intervening 7-10 years. Good financial habits, lower amounts of debt, and consistent repayments as applicable according to a bankruptcy filing can all help improve your score, though it won't reach the heights it was before for quite a while.

Well, assuming you haven't fallen into old habits and racked up even more debt you can't pay, chances are that your credit score has slowly been improving over the intervening 7-10 years. Good financial habits, lower amounts of debt, and consistent repayments as applicable according to a bankruptcy filing can all help improve your score, though it won't reach the heights it was before for quite a while.

When your bankruptcy finally falls off of your credit report, you will see some increase in your score. However, this might not be a "full" restoration for a few reasons.

Generally, when your bankruptcy falls off of your credit report, your score will increase, usually by somewhere between 30 to 100 points. This may seem like a huge increase, but it's still relatively small compared to the decrease that the bankruptcy caused in the first place.

It's entirely possible to recover to your previous score or even get a better score than before, but it will likely take quite a number of years. You need to not only let your previous debts, defaults, and bankruptcy age out; you need to establish a history of positive payments in the intervening time. You may be looking at 15-20 years before you can truly be considered recovered.

Yes, of course. However, some of the options available to most people will not be available to you. For example, here are several tips given to improve credit scores:

These are not generally available to you. When you declare bankruptcy, many of your existing lines of credit will be closed, and you will generally be denied for higher credit limits (since you've proven you can't handle what you have now). Likewise, opening a new line of credit for a balance transfer will generally be denied. Indeed, with a lower credit score and a bankruptcy on file, you will be denied for most lines of credit, and the ones you can get will have much worse terms.

If this seems unfair, well, it kind of is.

That said, there are still ways to improve your credit score even while your bankruptcy is still on file.

You can always work to improve your score, no matter what your financial situation may be.

Defaulting on a loan means violating terms and not paying it. When you default, the creditor may pursue you for payments, and they can even sue you for the balance. Alternatively, they can sell the debt to a collection agency and let them worry about it.